Are We There Yet?

by Martin J. Smith

Two authors, four kids, two minivans and a 6,500-mile journey into the world of self-promotion.By Martin J. Smith

We're rolling along the I-10 eastbound, chasing destiny in a rented

|

More importantly, we have a full 48-book box of my second novel, Shadow Image (Jove, 1998), a psychological thriller, and an ample supply of stand-up sales displays featuring the book's cover, each hand-made as an after-school project by my 9-year-old daughter Lanie and 6-year-old son Parker. We have 3,000 promotional postcards that I designed and paid for, and a detailed schedule of bookstore and media events organized by an independent Beverly Hills publicist I hired to help promote the second novel in my "Memory Series."

Even though Shadow Image was one of only 11 books cited in a Publishers Weekly story previewing recommended summer reading, I can't assume the book will sell. Silence equals death in crime fiction today, and I'm out to make some noise.

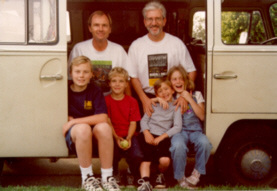

A quick glance in my rearview mirror lets me know I'm not alone. My friend and fellow author, Philip Reed, is rolling along behind us in a nearly identical minivan with his two sons, Andrew, a 12-year-old chess master, and Tony, an 8-year-old air-guitar impresario. Phil is promoting Low Rider (Pocket Books, 1998), the second novel in a "car noir" series The New York Times called "a volatile concoction of speed, sex and sleaze."

Together, as our wives back home work at the less risky jobs that sustain our families, we're barnstorming a circuit that will take us from Southern California in a counterclockwise 6,500-mile loop around the Western United States. Along the way, we intend to sign books for fans and read selected passages to anyone who'll listen. We'll pass out free copies to influential booksellers and exploit the novelty of our self-styled "Dads Tour" to attract local media attention. When things get slow, I'll play my harmonica as loudly as I can to attract a crowd in the larger stores.

In other words, we'll shed the mien of serious crime writers and become the literary equivalent of those human directionals who point giant foam-rubber fingers at model homes.

Not exactly what we had in mind when we began our careers, but reality for writers like us is as cold and hard as the bottom line: Critical acclaim is nice, but most publishers today measure success by sales figures. And so we're on the road -- Kerouac and Kesey for the '90s, as one Colorado bookstore owner dubbed us -- driving hard toward what might be a mirage, bestseller or bust.

"Are we there yet?" my impatient boy asks just 40 miles into the trip, and I tell him no, we aren't there yet. He focuses again on his Game Boy. I refocus on the horizon, but his question perches on my shoulder like a mockingbird. The answer is unavoidable: No, I'm not there yet.

Of all the advice given me during the years I struggled to launch this career, one conversation stands out. Shortly before publication of my first novel, I asked Newport Beach novelist Dean Koontz what it would take for a writer like me to break into the exclusive circle he now occupies with other bestselling authors such as Stephen King, John Grisham, Tom Clancy and Patricia Cornwell -- writers whose commercial success helped create the mirage that first coaxed me down this road. His answer was sobering: "Figure you've got five books to make it."

As Koontz explained, the publishing industry has changed since he started more than 30 years ago. Used to be, publishers gave talented writers time to develop an audience. And even if their books never became bestsellers, those writers could make a decent living writing so-called midlist books. But today, he said, the midlist is dwindling. Now most authors get five books in which to evolve from a flyspeck on the literary landscape into a 600-pound gorilla. Otherwise, publishers lose interest.

I now think the five-book estimate was wildly optimistic. More than 50,000 new titles will be published in the United States this year, about 1,400 of them in the broad genre known as mystery or crime fiction. Only a handful will break through to the bestseller lists. Some will get there because they're great books hand-sold by enthusiastic book store owners. Others will stink, but will get there anyway thanks to huge promotional budgets or an incomprehensible alchemy of topic, timing and public mood.

Then there are books such as Shadow Image and Low Rider, which arrive at stores like abandoned children. Mass-market paperback originals like mine have a normal life span only slightly longer than a mayfly -- between six and eight weeks during which they're reviewed, recommended by booksellers and displayed prominently in stores. If they haven't sold within that time, many stores will keep a copy or two, then strip the covers off the rest and ship them back to the publisher for a refund. The publisher carefully monitors what's called the sell-through rate -- the percentage of shipped books that actually sell. Generally, if a book's sell-through rate is less than 50 percent, the publisher starts to worry. It's brutal, and effective promotion is critical.

"The day I got my author copies of Bird Dog, I thought my job was finally done," Phil says of his first book. "I thought if the reviews were good I could sit back and the book would sell. But that was the very moment I needed to get my energy back up, to change gears and go out and promote. I realized if I didn't it might disappear without a trace."

That realization can be deflating, because it's tough to shed the literary-lion persona you projected in your author photograph, armor yourself with a crush-proof ego, and proceed with the determination of a door-to-door salesman. But watching your book crash in a cloud of critical acclaim is even tougher. "It seems to be almost accepted now in our genre that you're going to promote your own book and you're going to pay for it," says Baltimore novelist Laura Lippman, who this year won an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America, crime fiction's top honor. "And if you're not willing to do it, your publisher interprets it as, 'You're not that serious.'"

Accepting that reality is the first step on a very long road, but it's a step many beginners find difficult to take. "In 1986, when my agent told me she'd sold my first book, I thought, 'What color Jaguar should I get?

Should I get my hair done for the Tonight Show?'" recalls Joan Hess of Fayetteville, Arkansas, author of more than 20 mystery novels. "And that was with a $2,000 advance and a publisher that wouldn't send me to the mailbox. You discover reality in your first conversation with your editor. If that leaves any idle hopes, a conversation with [the publisher's] publicity department will take care of it."

Says Long Beach crime author Jan Burke: "You can either become like one of those guys in jail who blames his attorneys, or you can do your best to promote the book yourself."

Truth is, many bestselling authors spent years and staggering amounts of time and money promoting their work before their books broke through, including James Ellroy, Michael Connelly and Burke. In fact, at the same time Ellroy was calling my first book an "astonishingly accomplished...whipcord thriller," the author of L.A. Confidential and other international blockbusters also was advising me to take every cent my publisher paid me and spend it for promotion, as he had done with his earliest books.

For crime writers, promotion has been made easier by the proliferation of independent mystery bookstores during the past decade. From a few stores in the late 1970s, the number has grown to more than 100 today. Getting to know those store owners has become one of the most effective ways for crime writers to cultivate an audience. Their enthusiasm and mailing lists can bring a book to the attention of voracious readers whose tastes cover all of the subgenres of crime fiction.

"My customers read a book in one or two days and then they come looking for something else," says Joan Wunsch, owner of Coffee, Tea & Mystery book store in Westminster. "And they trust my judgment to find them something they'll like."

Getting out to meet store owners like Wunsch costs money that most publishers don't offer to beginners, but many consider the effort and expense a long-term investment. Connelly, whose most recent books have become national bestsellers, says the success of his seventh book [Blood Work] "has a lot to do with the ground work I did on the first few books. The best way to build an audience is to write good [stories], get good reviews, and get some word-of-mouth going. You can help a lot with that if you're out there putting the books in people's hands."

Crime writers are doing that in increasingly creative ways. Some organize what Hess calls "dog and pony shows" to take on the road. Others schmooze booksellers at trade shows and conventions, hawk books on personal web sites, pool resources to get the best travel deals. (Burke says she and fellow Long Beach writer Wendy Hornsby once used Southwest Airlines' "Friends Fly Free" program as the basis of a joint promotional tour.) Authors now bake cookies and hand them out at signings, auction T-shirts, raffle door prizes, wear costumes or otherwise behave like slicer-dicer hucksters on late-night infomercials. I have personally witnessed a writer perform a three-minute tap-dance routine to promote her nonfiction book about tap-dancing.

"Mystery writers have shown the rest of the world how to do it," says Dulcy Brainard, mystery forecast editor for Publishers Weekly, the dominant publishing-industry trade publication. "It's a testament to their feisty spirit as a group that they didn't waste their time beating their breasts and pulling their hair out saying, 'Poor me!' They figured out a way to do something about it."

Facing overwhelming odds against break-out success, many crime writers also develop a sort of wartime camaraderie, exchanging the names and numbers of bookstore contacts, graciously sharing the stage at conferences and workshops, writing cover blurbs for one another's books. I benefited from advice or advance praise generously offered by Koontz, Connelly, Ellroy, T. Jefferson Parker and others. In turn, I adopted their karmic sense of goodwill toward writers who are following me down this same road.

Phil and I met last October at a mystery convention in Monterey. After speaking together on a panel of first-time novelists, one of whom had spent more than $40,000 promoting a book for which he received an $8,000 advance, we retreated to lunch and decided there had to be a better way. We'd already discovered that instant success was an illusion, and that promotion was a do-it-yourself job. But we also knew the critical and commercial success of our first books had given us a precious head start. My first novel, Time Release, recently went into a third printing and was a finalist for a prestigious crime-fiction award. Phil's first, Bird Dog, sold out its first printing and was a finalist for two awards. The performance of our second books, due out in June, was either going to move us closer to the mirage, or further from it.

The solution, we decided, was to do something completely nuts.

When we arrive at Tucson's Clues Unlimited for the first of more than 50 store and media events on the Dads Tour, my minivan looks less like a sophisticated mobile entertainment complex than a rolling garbage scow. Maps, fast-food wrappers and Game Boy cartridges litter the passenger compartment. It's impossible to open the doors without stuff falling out. The front grille features the start of a squashed-bug collection that, three weeks later, would prompt someone in San Francisco to note: "Scrape that stuff off, you could make a nice soup." And that was long after my son removed the hummingbird.

Phil, pathologically neat, rolls in a few minutes later in a van that looks showroom fresh, Gallant to my Goofus. We are ushered to a table piled high with copies of our books and survey the store. We are, we notice, the only people present who do not actually work there.

"It's this heat," explains Charlene Taylor, one of the store's owners, referring to the 105 degrees outside.

As a crime writer, you are the Master of the Universe. Characters behave as you wish. You reward good, punish evil, dispense justice in appropriate measure. But as a self-promoter, you control nothing. Worse, you can't even imagine all the things beyond your control -- including the weather -- that might affect your literary career. As our little caravan traverses the Southwest, playing to welcoming booksellers and small crowds, we realize that our tour coincided precisely with what scientists now say was the hottest July since reliable record-keeping began.

At one southern Colorado store, the resident cat attracts a larger crowd than we do during the 90 minutes we spend disassembling and reassembling our signing pens. Exasperated, we later ask a Barnes & Noble sales clerk in Denver what she feels is the best way to promote a book. "TV," she said. "You know, Oprah, Good Morning America. That sort of thing really helps."

Last we checked our messages, neither had returned our calls.

We soldier on, looking ahead to appearances in the Pacific Northwest, with its reputation for rain and reliable gloom. But the heat wave continues and the crowds, though enthusiastic, remain thin. We make the best of it, but at night, as we watch our kids cooling down in motel pools, Phil and I ponder whether the success or failure of our books might be determined less by our skill at creating memorable characters and fast-paced plots than an unexpected hot spell.

We'd already realized that the weather was just one of many critical factors beyond an author's control. Five days into the trip, Phil noticed that his book wasn't as widely distributed as he'd expected. It was always at stores where it was special-ordered for our appearances, but often not available at chain stores where we did "drive-by signings" -- brief stops to chat with the store manager and sign whatever books were in stock.

Had someone screwed up the distribution? Or had the chains' centralized ordering staffs simply passed on the book? These are troubling questions when you're halfway into a self-financed 6,500-mile tour, the kids are cranky, your gas credit cards are worn thin and you haven't eaten anything but fast food for weeks. Besides, it made no sense considering the success of Phil's first book. "The worst thing was I couldn't get a straight answer out of anyone," he says.

As writers, we were prepared to have our egos crushed by critics. As self-promoters, we were willing to become the Barnum & Bailey of American letters. But Phil made a seemingly safe assumption before spending thousands of dollars to promote Low Rider -- that his book would actually be in stores -- and he wasn't at all prepared to have that assumption crushed like a bug on a minivan windshield.

Confronted by a problem too large for us to solve, we pondered our future one sweltering day in Seattle as we ordered another round of burgers at a Jack-in-the-Box drive-through. The sign on the window read "Ask us about career opportunities" and we thought, hmmm.

One grueling day after two weeks on the road, we saw a vivid demonstration of how overmatched our books were among the flurry of summer releases. A segment on CBS' 48 Hours featured author Nicholas Sparks, whose second novel, Message in a Bottle, debuted this summer to mixed reviews. The segment described how Warner Books -- the same publisher that in 1992 made book-marketing history with The Bridges of Madison County -- launched a no-holds-barred, megabuck marketing campaign to put Sparks' first book on national bestseller lists. The CBS feature about that earlier campaign was perfectly timed to boost Sparks' second book onto national bestseller lists, and in that strategy I sensed the work of a promotional genius.

The Dads Tour, on the other hand, sometimes seemed like the work of a TV sitcom writer. The day before our Clues Unlimited appearance, for example, Phil and I agreed to call Tucson radio host John C. Scott from separate pay phones shortly before noon so we could appear simultaneously on his KTKT-AM talk show. I chose a secluded bank of phones at an elegant resort and convinced my kids to keep absolutely silent while I was on the air. They cooperated beautifully, but just as we went live one of the resort's day-care workers ushered a gaggle of pre-teens into the nearby bathrooms.

It sounded like I was calling from prison.

Without my wife's steely sense of law and order, the civilization inside our minivan quickly degenerated into anarchy, Lord of the Flies on wheels. At Page One in Albuquerque, New Mexico's largest independent bookstore, my kids disappeared into the children's section while I spoke to a dozen or so people in the center of the store. The main character of my books is a memory expert, and I was deep into my explanation of the vagaries of human memory in criminal justice when the reactions of the audience seemed a little off kilter. People were laughing. I turned to find my 6-year-old son engaged in a spirited puppet show from behind a low wall. Like a rubber-faced Chevy Chase to my somber Jane Curtin, the dragon he'd found was mimicking my every word and gesture.

At a store in Bellingham, Wash., our raucous little horde swarmed through the doors, overwhelming a staff that until then had found the Dads Tour idea rather charming. My daughter was well into the second verse of a favorite song on the store's sound system when a nervous manager unceremoniously snatched the microphone from her hands and urged us to begin our talk.

By then, Phil and I were wondering what possible difference our efforts could make. And yet in that isolated northeastern corner of the United States a thousand miles from home, a stranger came by on a Saturday afternoon and introduced himself. He'd read and enjoyed Bird Dog, Phil's first book, and brought his copy for Phil to sign. He bought a copy of Low Rider and had Phil sign that, too, genuinely grateful for the chance to talk to the books' author. We realized then that, in our headlong rush toward the mirage, we'd lost sight of something real: the passion and reverence that many people still reserve for books.

"Seeing that firsthand was enormously gratifying," Phil said later.

Things changed for us that day, and for the rest of the trip through Washington, Oregon and Northern California, we focused on the journey instead of the destination. If we accomplished nothing else, we decided, at least we were spending a month together with our children. I took my kids on side trips to the Grand Canyon, Mount Shasta, and to camp in Yellowstone; Phil and his kids detoured through the mountains of southern Colorado, Id aho's Sawtooth Valley, the Oregon coast. We'd shown them that the world extends far beyond our neighborhoods, that it's filled with fascinating people, including some who can decorate cakes to look like book covers and others who invite road-weary strangers into their homes. That alone was priceless.

We never again lost sight of what our years of effort had wrought. We each had two books in print, a privilege relatively few writers get. We're earning a living doing what we love. Our books are being favorably featured in reviews, newspaper stories, radio broadcasts and TV interviews. If at this point we're unable to push Shadow Image and Low Rider onto bestseller lists -- and in retrospect that seems a hopelessly naive goal -- at least we were meeting hundreds of people who enjoyed our books and are looking forward to the next ones. We had the chance to introduce our work to hundreds more and encourage unpublished writers who saw hope for themselves in our modest success.

Ultimately, Phil and I accepted the idea that we're doing everything we can to help our books succeed, and that, for now, it's all we can do. And that's a good thing to remember when you're headed for home but not quite there.

The minivan I am about to turn in to a rental agent at Long Beach Airport is undamaged, but far different than the one my kids and I picked up four weeks before. We've nearly quadrupled the odometer reading. The front end looks like a Jackson Pollock masterpiece. In the road dust on the rear window, various promotional slogans and the names of the Dads Tour participants are inscribed in our children's handwriting.

"You can't wash it now," Phil had said one day late in the trip. "It's like folk art."

I unload the duffel bags and camping equipment, then drain the cooler. I shovel out the spent batteries, broken Kids Meal prizes and the toxic detritus of the road. I empty the glove compartment of its dense clot of maps, Triptiks and Auto Club travel guides, and place the minivan rental agreement into the empty cavern that remains. The last thing I remove is a Native American souvenir my kids bought in Santa Fe. It had dangled from the minivan's rearview mirror since the first week of the trip, an odd assembly of leather, feathers, beads, and webbing called a Dream Catcher.

According to Native American legend, the night air is filled with dreams. A Dream Catcher hung just above one's head can capture those dreams. Good dreams slip through a hole at center of the web, and those you get to keep. Bad dreams get tangled in the web and perish with the first light of a new day. The Dream Catcher instructions say, "Native Americans believe that dreams have magical qualities, the ability to change or direct one's path in life," and I believe that, in many ways, the magic already has worked for me.

But as I close the minivan door for the last time, I wonder if the ancients ever envisioned a chase vehicle quite like this.

**Award-winning journalist and author

Martin J. Smith, 42, is a veteran journalist and magazine editor. He has won more than 40 newspaper and magazine writing awards, and four times was nominated by his newspaper for the Pulitzer Prize.

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,

he began writing professionally while a student at

Pennsylvania State University in the late 1970s. His

15-year career as a newspaper reporter took him around

the world, from the rural poverty of Southwestern Pennsylvania

to Nevada's Mustang Ranch bordello; from the riot-torn streets

of Los Angeles to the revolutionary streets of Manila; from

pre-glasnost Siberia to the new frontier of cyberspace. He

currently is editor-at-large of Orange Coast magazine in Orange

County, California, a regional monthly magazine he edited for four

years.

His Anthony Award-nominated first novel,

Time Release (Jove, 1997), which just went into its third printing,

featured memory expert Jim Christensen and examined

the volatile issue of repressed memories against the backdrop of

a sensational product-tampering case. The story, set in Pittsburgh,

was conceived as the 10th anniversary of the infamous Tylenol

killings neared and inspired by a rash of repressed-memory

prosecutions during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

In

Shadow Image (Jove, 1998), a sequel inspired

by the plight of former President Ronald Reagan, Christensen

is drawn into the labyrinth of Alzheimer's disease and a

complex web of lies created by one of Pennsylvania's wealthiest

and most powerful political families. Martin J. Smith's

third novel, Straw Men, will be

published by Jove in 1999.

He lives with his wife and their two children in

Southern California, where he remains part of what he feels is

an often

overlooked minority -- the Soccer Dad. Philip Reed is working

on his third novel.

**Award-winning journalist and author

Martin J. Smith, 42, is a veteran journalist and magazine editor. He has won more than 40 newspaper and magazine writing awards, and four times was nominated by his newspaper for the Pulitzer Prize.

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,

he began writing professionally while a student at

Pennsylvania State University in the late 1970s. His

15-year career as a newspaper reporter took him around

the world, from the rural poverty of Southwestern Pennsylvania

to Nevada's Mustang Ranch bordello; from the riot-torn streets

of Los Angeles to the revolutionary streets of Manila; from

pre-glasnost Siberia to the new frontier of cyberspace. He

currently is editor-at-large of Orange Coast magazine in Orange

County, California, a regional monthly magazine he edited for four

years.

His Anthony Award-nominated first novel,

Time Release (Jove, 1997), which just went into its third printing,

featured memory expert Jim Christensen and examined

the volatile issue of repressed memories against the backdrop of

a sensational product-tampering case. The story, set in Pittsburgh,

was conceived as the 10th anniversary of the infamous Tylenol

killings neared and inspired by a rash of repressed-memory

prosecutions during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

In

Shadow Image (Jove, 1998), a sequel inspired

by the plight of former President Ronald Reagan, Christensen

is drawn into the labyrinth of Alzheimer's disease and a

complex web of lies created by one of Pennsylvania's wealthiest

and most powerful political families. Martin J. Smith's

third novel, Straw Men, will be

published by Jove in 1999.

He lives with his wife and their two children in

Southern California, where he remains part of what he feels is

an often

overlooked minority -- the Soccer Dad. Philip Reed is working

on his third novel.

"Are We There Yet" first appeared in the Nov. 1, 1998 issue of L.A. Times Magazine. Copyright © 1998 by Martin J. Smith. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission.

Return to the January 1999 issue of The IWJ.